From Tent View to 2025’s Epic Climb – Ponsonby Interview

The summit of Aikache Chhok. Photo: Ponsonby/Price

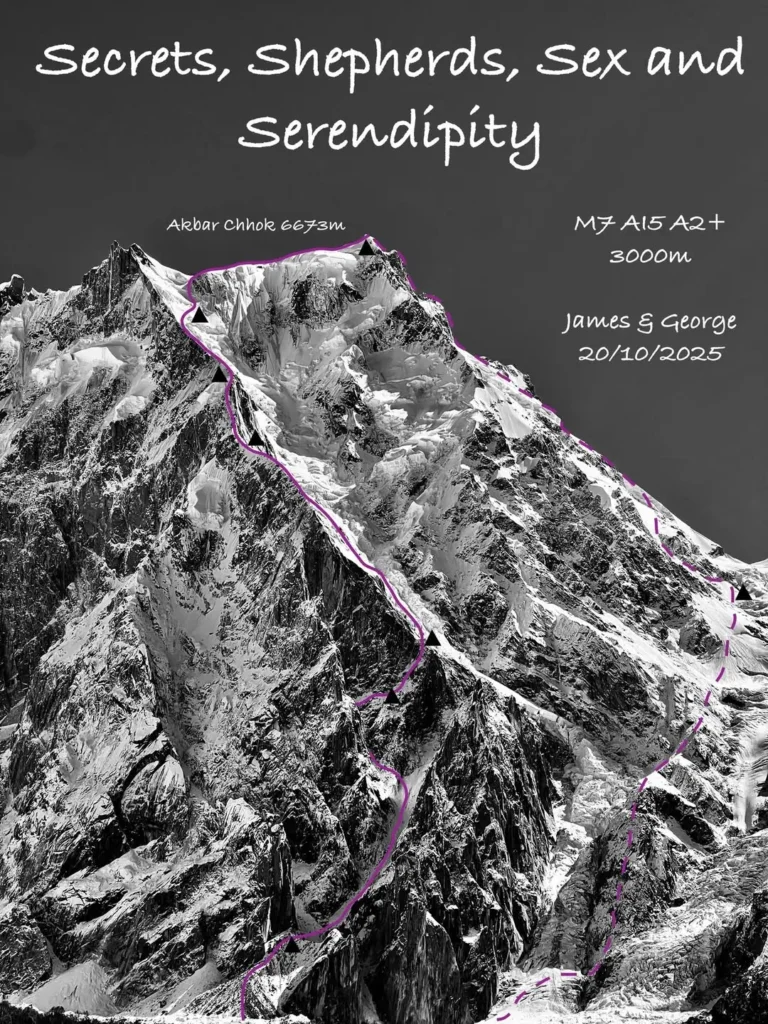

In October 2025, two young alpinists from the British Young Alpinist Group slipped quietly into Pakistan’s remote Baltar Valley and pulled off what many are already calling one of the finest alpine climbs of the year. George Ponsonby (29, Ireland) and James Price (28, England) spent nine committing days establishing “Secrets, Shepherds, Sex and Serendipity” (M7, AI5, A2+, 3000 m) on the northwest ridge of the rarely visited 6673 m Aikache Chhok. We caught up with George shortly after the ascent to hear the full story in his own words.

From a 15-Minute Idea to the Karakoram

The trip began almost as a joke. “We were in Scotland on a YAG trip last January, and everyone was asked to come up with an expedition idea,” George remembers. “James and I spent about 15 minutes coming up with ideas and making a presentation… Somehow James’ got voted as the first choice.” Neither of them expected the half-baked plan to win, but it did – and suddenly they were committed to Pakistan.

Preparation was far from ideal. James injured his ankle tendon weeks before departure and packed a ski boot as a contingency. George spent the summer commercial salmon fishing in Alaska from 6 am to 11:30 pm every day. “That meant no climbing and no uphill training since the end of June,” he laughs. “The job is really physical… but it’s not climbing muscle.”

By the time they reached the Baltar Valley with teammates Sinead Thin, Gemma Robertson, Anna Soligo and local climbers Hassan, Adnan and Najeeb, ambitions were modest. Then James’s ankle miraculously improved, George felt fitter than expected, and the weather gave them a window.

The Line Outside the Tent Door

Base camp sat among friendly Wakhi shepherds in flowering meadows. Every morning the pair opened their tent to the same view: a long, complex northwest ridge rising straight above camp. “We basically chose the line we could see outside our tent each morning!” George says. “We’d spent a week and a half in basecamp scoping out potential routes… but that ended up being the most appealing in terms of safety (lots of seracs around), looking like it had technical climbing, and aesthetics.”

They left on 13 October with food for five days and fuel for seven. What followed was pure adventure.

The first day felt promising – good progress up a main gully, then mixed pitches to within three leads of the ridge. Day two delivered the reality check: three desperate pitches all day, including aid climbing on an overhanging, increasingly loose crack that pushed the grade to M7/A2+. “The ambiance had become a little too ‘Grandes Jorasses-ey’ for our liking,” George recalls.

Day five became the crucible. After a dead-end traverse the previous evening and a disastrous attempt at making “mango-tasting, plastic-like custard,” the pair reorganized their strategy. George took the light lead bag and moved as efficiently as possible while James managed the seconding and logistics. Together, they fought through eight full-length pitches of bulletproof AI5 glacial ice, most of them 60-metre rope stretchers, finishing the final pitch by headlamp.

Day six brought a new horror: almost 1,000 metres of black ice rising above them on the ridge. Exhausted and with battered feet, they perfected what they jokingly called the “Karakoram flop” – a desperate technique for hauling themselves over vertical blobs of snow when too tired to front-point.

On day eight, after a freezing storm-bound bivouac just below the summit cornice, they shared their last energy bar, climbed the final pitches, touched the top and immediately turned their full attention downward. “Touching the summit just felt like a box-ticking exercise,” George admits. “The climb was done… I was more stressed about losing 20 minutes of descent time.”

Photo: Ponsonby/Price

The Descent – Where James Shines

If the ascent was demanding, the unknown southwest face descent was terrifying. Clouds had hidden it completely from base camp. “Tough descents are where James really starts to shine,” George says with obvious respect. “For me, along with the climbing James is incredibly dialed at just surviving in the mountains… organising bivvys, having a good perspective at how much further you can really push yourself… and really good at navigating complex glacial terrain, tricky descents etc.”

After summiting on the morning of Day 8, George and James immediately began the descent – onsighting a complex, unseen route down the southwest side of the mountain. The pair rappelled off rock, built endless V-threads, and threaded their way through seracs and heavily crevassed glaciers. They finally reached a safe bivouac spot at around 5,000 m at sunset on Day 8, where they saw the comforting glow of headlamps flashing up at them from Base Camp.

On Day 9, they continued down a long rock rib, sprinted beneath threatening seracs, and completed the last exposed section of the descent – including a short but tricky ice step to regain the lower glacier. By mid-afternoon, they were finally off the mountain.

Shepherds, Serendipity and a Bollywood Name

The shepherds had watched the entire climb through binoculars, flashing head torches each night in encouragement. Local host Akbar lent the team a stone hut and supplied fresh milk daily. In return – and because no one in camp knew of the 1983 Italian south-face ascent – they gifted the peak the honorary name “Akbar Chhok” from the Baltar side.

The route name? Pure base-camp silliness. “There’s honestly not too much of a deeper meaning behind the name,” George laughs. “We spent far too long coming up with a silly Bollywood-style screenplay in basecamp with that as a title… it just kind of stuck after that.”

Looking Back – and Forward

When asked what the climb means to him, George keeps perspective: “It’s hard to say what it means to me personally – just incredibly glad we were able to do it, happy to be off safe, and it felt good that we had the knowledge and skills to make it happen. It was a step up for both of us, and you’re never quite sure if you’re up for it before routes like this.”

At 28 and 29 years old, both climbers have many big mountains ahead. But for nine October days in the Baltar Valley, with little more than friendship, a tent-door view and a lot of shepherd chai, George Ponsonby and James Price reminded the alpinism world what lightweight, improvisational adventure still looks like in 2025.

Comments