Eiger 1936: The Last Hours of Toni Kurz

Some mountaineering stories become legends not because they end in triumph, but because of how deeply they touch the human spirit. The 1936 tragedy on the Eiger North Face – the dreaded Eigerwand – is one of those stories.What happened over those few days in July is a mixture of raw courage, fatal decisions, and a rescue attempt that came agonizingly close to succeeding. At the center of it is Toni Kurz, a young climber whose final sentence – “Ich kann nicht mehr” – became one of the most haunting lines in mountaineering history.

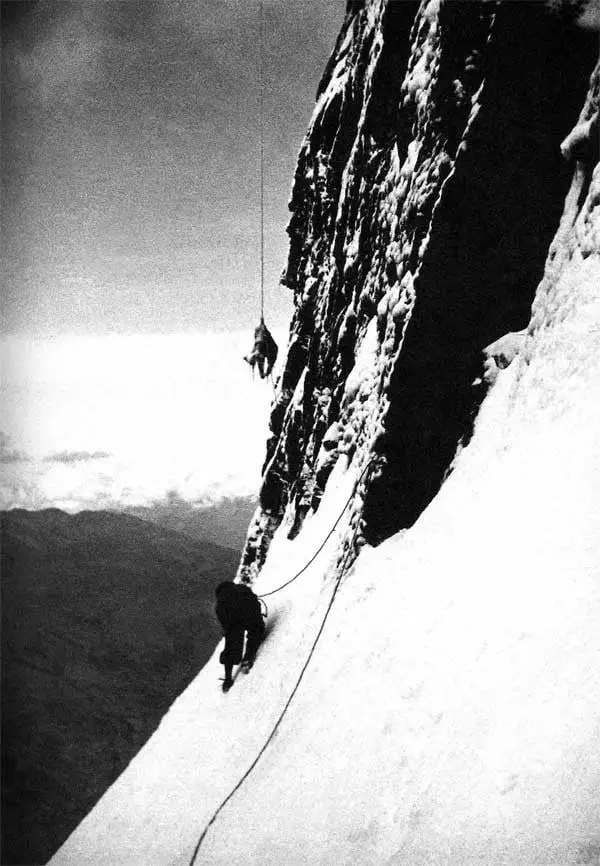

The salvage team were met by the terrible sight of the ice-covered corpse of Toni Kurz. Photo: Rainer Rettner Interview

The Impossible Wall

The story of Toni Kurz on the Eiger North Face is one of the most haunting, heartbreaking events in mountaineering history – a tragedy that unfolds like a slow-motion nightmare on Europe’s most feared wall.

But long before he hung frozen above the rescuers, Toni Kurz was a young man shaped by the mountains.

Born on January 13, 1913, in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, he grew up in the shadow of steep Alpine cliffs, where climbing wasn’t a sport – it was a way of life. At just sixteen, he completed an apprenticeship as a metal worker (Schlosser), a trade that made him precise, strong, and mechanically gifted – skills that would later serve him on the mountain. In 1934, he joined the Gebirgsjäger, the elite German mountain infantry. The military sharpened his physical endurance, discipline, and confidence in extreme terrain.

His closest climbing partner was Andreas Hinterstoisser, also from Berchtesgaden. The two were inseparable – young, bold, technically gifted, and rapidly becoming legends in the local climbing community. Together they opened new, daring routes in the Berchtesgaden Alps, routes so severe they remain classics even today.

In July 1936, Kurz (23) and Hinterstoisser (24) set their eyes on the ultimate challenge: the unclimbed North Face of the Eiger – “Die Mordwand,” the Murder Wall.

They teamed up with two Austrian climbers, Willy Angerer and Edi Rainer, both strong and experienced. The four men famously rode bicycles from Bavaria to Switzerland, arriving in Kleine Scheidegg with minimal gear but enormous ambition.

The wall in front of them was 1,800 meters of cold limestone, collapsing icefields, avalanches, and storms that formed in minutes. No one had climbed it. Several had already died trying. The face had become the most terrifying unclimbed challenge in the Alps.

Still, the four young men stepped onto it with courage and determination.

The Storm and the Retreat

The ascent began well on July 18, 1936. Moving confidently over steep rock and ice, the group reached the smooth, notorious limestone slab that had repelled previous attempts. It was here that Hinterstoisser performed one of the most brilliant moves in the history of alpinism – a breathtaking diagonal traverse across a blank, polished wall. Using extraordinary strength and balance, he crossed and fixed a rope so the others could follow.

That move became the legendary Hinterstoisser Traverse.

But in their optimism, the team made a decision that would later become an infamous mountaineering lesson:

they pulled down the rope after crossing.

Believing the upper face would go smoothly, they expected to descend by a different route.

They could not imagine the storm brewing above them.

Soon the weather broke. Snow turned the slabs into frozen glass. Visibility collapsed. The freezing winds made the rock brittle. And then tragedy hit: Willy Angerer was struck by falling rock or ice, severely injuring his leg. His pace slowed dramatically. Continuing upward was impossible.

The only choice was retreat. But when they reached the Hinterstoisser Traverse again, they found the unimaginable: the slab Hinterstoisser had crossed the day before was now coated in verglas – impossible to cross without the rope they had removed. They were trapped.

The storm worsened, the walls iced over, and the team attempted a desperate descent through gullies and overhangs normally avoided. The mountain began taking its toll with brutal speed.

Hinterstoisser, exhausted and battling the storm, slipped and fell to his death. Angerer, unable to move and gravely injured, succumbed to exposure. Rainer, lowering Angerer during the retreat, was pulled off his stance when the rope system failed – both men fell.

In less than an hour, three climbers were gone.

Only Toni Kurz remained alive – suspended, alone, in the middle of the Murder Wall.

The Rescue Attempt

From the village of Kleine Scheidegg, locals watching through telescopes saw a single figure – Kurz – hanging high on the wall. A remarkable rescue attempt was launched by Swiss guides such as Christian Almer Jr. and Hans Schlunegger, climbing through the dangerous Eiger railway gallery to reach the base of the face.

When they finally came within shouting distance, Kurz answered them – astonishingly calm despite the cold, the altitude, and the trauma. He described in detail how each of his partners had died. His voice carried through the storm.

The rescuers urged him to descend. With one hand frozen stiff, Kurz used the other to cut away the dead bodies from his rope system and lower himself, knot by knot, toward the rescuers. It was a superhuman effort: a climber near hypothermia, alone on the wall, exhausted and grieving, lowering himself through a tangled set of ropes in a blizzard.

Hour after hour, he descended, reaching the final knot – the last section of rope between him and the rescuers.

They shouted for him to continue. They held out their rope.

Then came the cruelest twist in the story:

The rope he was on was too short.

The knots he had tied to connect the damaged ropes made the final length too short for him to reach the rescuers. He tried swinging. He tried pulling himself lower. He tried to free another length of rope. But he had nothing left.

He had been on the wall for nearly two days. He was freezing, exhausted, and alone.

Finally, in a quiet, almost peaceful voice, Kurz spoke the words that echo in mountaineering history:

“Ich kann nicht mehr.” “I can’t go on.”

Moments later, his body went still.

He died hanging just meters above the rescuers – close enough to see, but not close enough to save.

Legacy of a Tragedy

Toni Kurz was just 23 years old when he died on the Eiger. His bravery and composure during his final hours transformed him into a symbol of courage and tragedy in the mountains. The 1936 disaster shocked Europe. Newspapers reported every detail. The Eiger North Face became legendary – not for triumph but for the story of four young climbers who gave everything they had.

The tragedy inspired books (including Heinrich Harrer’s The White Spider), documentaries, and films. Climbers today still pass the spots named after those final moments: the Hinterstoisser Traverse, Rainer’s Overhang, and Kurz’s Last Stand.

The story remains a powerful reminder that heroism in mountaineering is not always found on summits.

Sometimes it is found in the final moments of a climber who refuses to give up – even when the mountain has already decided his fate.

Comments