Everest 1924: The Summit Mystery Lives On

A century later, the disappearance of George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine on Mount Everest remains one of the most enduring mysteries in mountaineering. Their 1924 attempt predates modern climbing gear, weather forecasting, and supplementary oxygen systems as we know them today – yet some historians still believe they may have stood on the summit long before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953. This is the story of that iconic expedition, the clues left behind, and the unanswered question that still grips the climbing world:

Did Mallory and Irvine reach the top of Everest?

Mallory (left) and Irvine in their last known photo. Photo: by Alamy

A Mountain the British Were Determined to Conquer

In the 1920s, Mount Everest was far more than a geographic high point; it was a symbol. For post-war Britain, still rebuilding its pride, Everest represented the ultimate test of national will. The first two British expeditions of 1921 and 1922 had revealed the route from Tibet, mapped the North Col, and proven that altitude near 8,200 meters was survivable. But the summit still stood untouched – remote, icy, and defended by brutal weather.

By 1924, one figure embodied Britain’s determination: George Mallory, already a legend for his grace on rock and ice. Mallory was elegant, charismatic, and poetic in the way he spoke about mountains. When asked why he wanted to climb Everest, he famously replied: “Because it’s there.” This time, he returned with a bold plan, a team of seasoned climbers, and a young Oxford athlete and engineering prodigy named Sandy Irvine, whose mechanical skill with the primitive oxygen equipment made him an unlikely but crucial partner.

Mallory & Irvine: The Unusual Summit Pair

Mallory was 37- experienced, weather-worn, and carrying years of longing to stand on the world’s highest point. Irvine was only 22, strong and enthusiastic but with little high-altitude experience. Yet he possessed something the expedition desperately needed: an ability to repair and optimize the oxygen systems that had repeatedly failed the team.

From the moment they met, Mallory admired Irvine’s energy and dependability. And as the expedition progressed, he became convinced that this young climber was the ideal partner for a fast, oxygen-assisted summit push. Other climbers were surprised by the pairing, but Mallory made it clear:

“I can’t see myself going to the summit without Sandy.”

A Season of Fading Chances

The team’s first summit attempts pushed the limits of what was then believed possible. Colonel Edward Norton and Howard Somervell made a bold oxygen-free climb, reaching a staggering 8,573 meters-an altitude record that would stand for nearly three decades. Norton came within sight of the Great Couloir, and for a brief moment, the summit seemed achievable.

A second attempt by Mallory himself, climbing with Geoffrey Bruce, was turned back by weather and oxygen failure. The monsoon was creeping closer. Most climbers believed the season was ending.

But Mallory refused to leave without one last try.

The Morning of June 8, 1924

Mallory and Irvine spent the night at Camp VI, perched at approximately 8,150 meters on the Northeast Ridge. Early on June 8, in the pale blue light of dawn, they left their tent and began climbing upward with oxygen apparatus on their backs. They moved slowly at first, a tiny pair of silhouettes against an ocean of snow and sky. Below them, the expedition’s geologist and strong climber Noel Odell was making his way toward Camp VI to support their descent. He was the last person to ever see them alive.

Shortly before 1 p.m., the clouds that had smothered the upper mountain suddenly tore open. Through the window of clear air, Odell saw two figures “moving strongly” toward one of the great rocky steps on the ridge – either the First or Second Step. For years he wavered on which step he had seen. But in his first, most confident account, he believed they were near the Second Step, astonishingly high on the route, and climbing well. Then the clouds closed again. This moment – Odell’s fleeting sight of the pair – became the core of one of mountaineering’s greatest mysteries.

Disappearance on the Upper Ridge

By evening, the support team knew something was wrong. Mallory and Irvine were overdue, and no one had seen any movement on the ridge. The next morning, Odell cautiously climbed up to their high camp. He found the tent battered, with their sleeping bags inside, untouched since they left. There were no tracks leading downward. No sign of a struggle. Just a silent, wind-scoured ridge. Mallory and Irvine had vanished into the high world of cloud and storm.

Clues Frozen in Time

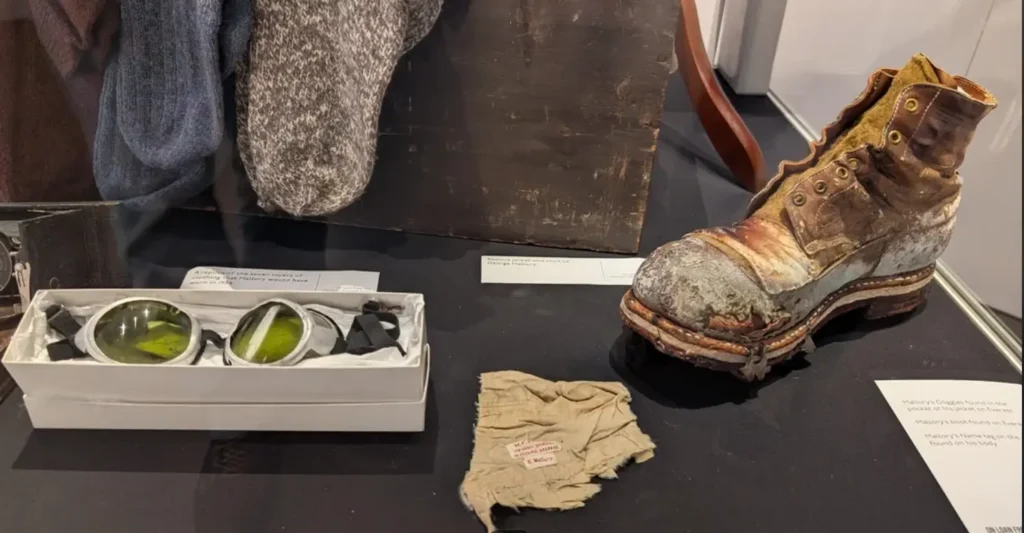

For decades, the mystery only grew. The next major clue emerged in 1933, when climbers Percy Wyn-Harris and Eric Shipton found Irvine’s ice axe lying on a ridge near 8,460 meters. Its location suggested the pair had climbed significantly above Camp VI before some event forced a catastrophic fall or retreat. Still, neither body was found. The mystery deepened.

Then in 1999, an American expedition led by Eric Simonson and with climber Conrad Anker made the discovery that electrified the mountaineering world.

They found the body of George Mallory, remarkably preserved, lying face-down on a steep slope at 8,155 meters. Mallory had severe injuries consistent with a major fall. A rope had snapped around his waist. His goggles were in his pocket, suggesting he may have been descending in fading light.

But the most striking detail was what they didn’t find:

the photograph of his wife, Ruth, which he had promised to leave on the summit.

It was nowhere on him.

And still, the most important object of all- the camera Irvine had carried, whose film might reveal summit photos – remained missing.

Somewhere, hidden under snow and ice, the truth still sleeps.

Did They Reach the Summit?

Experts remain divided.

Those who believe they succeeded argue that Mallory was one of the finest climbers of his generation, and with Irvine’s oxygen support, they could have moved quickly. Odell’s sighting shows they were climbing well high on the ridge. The missing photograph fuels hopes that they stood on the top before tragedy struck during the descent.

Those who doubt it point to the Second Step – a formidable, almost vertical rock barrier. Without modern gear, fixed ropes, or the ladder installed in 1975, it may have been impossible. The weather was unstable. Their oxygen sets were unreliable. Their clothing was primitive.

And yet, no theory can fully explain everything we know. Every piece of evidence opens new questions instead of closing old ones.

That is why this mystery endures.

The Legacy of Mallory & Irvine

George Mallory and Sandy Irvine represent an era of exploration defined not by technology but by sheer determination. Whether they reached the summit or not, they pushed the limits of human endurance at a time when Everest was still untouched and largely unknowable.

Their story is not just about a climb – it is about obsession, courage, national identity, and the irresistible pull of the unknown.

To this day, mountaineers climbing the Northeast Ridge look up and imagine those two faint figures moving upward through the clouds, toward a summit no one had ever reached.

Perhaps they stood on the top.

Perhaps they came heartbreakingly close.

Perhaps the mountain claimed their secret forever.

But one thing is certain:

The mystery of 1924 remains one of the greatest stories in mountaineering history.

Comments