Nanda Devi Reopens: India’s Iconic Peak Returns in 2025

After 42 years, India is preparing to lift the mountaineering ban on Nanda Devi, its second-highest and most sacred peak. This story unpacks the mountain’s hidden history, ecological recovery, cultural significance, and what reopening now means for climbers, locals, and the fragile Himalayan environment.

Table of contents

A Peak Steeped in History and Myth

Why Was Nanda Devi Closed?

Georgian Presence on Nanda Devi East’s New Route Attempt

Reopening in 2025: What’s Changing

What This Means for Mountaineers

Environmental Concerns: Can It Be Sustained?

Local Impact and Jurassic‑Opportunity

Looking Ahead: A New Chapter with Caution

A Peak Steeped in History and Myth

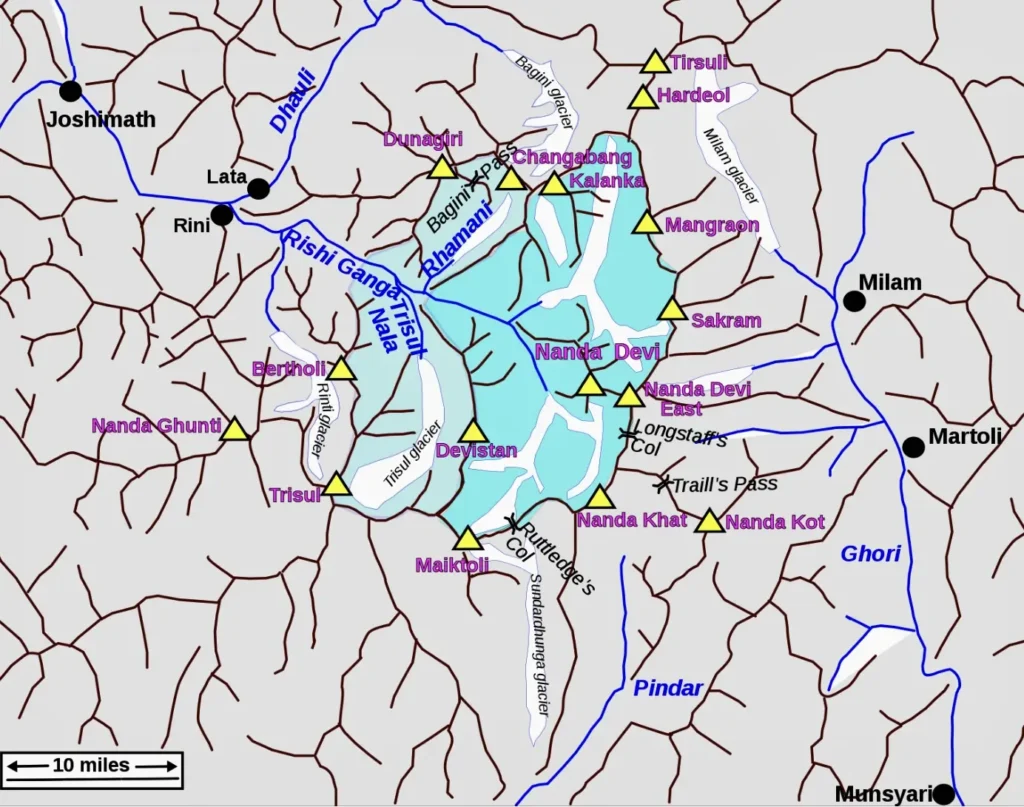

Nanda Devi (7,816 m) is the second-highest mountain in India after 8,586 m Kangchenjunga, and the highest located entirely within the country. Known as the “Blessed Goddess,” Nanda Devi has a slightly lower eastern twin, Nanda Devi East (7,434 m), also called Sunanda Devi. A nearly 3‑kilometer-long ridge, rising close to 7,000 m, links the two summits, forming the celebrated “twin peaks of the goddess Nanda.

From its southwestern base, Nanda Devi rises more than 3,300 m, dominating the surrounding landscape both physically and spiritually. In Garhwal’s Hindu tradition, Nanda is considered the most important deity of the region. “She permeates the whole area,” wrote Hubert Adams Carter, American mountaineer and former editor of the American Alpine Journal, in 1977. “In the region drained by the Rishi Ganga and the Dhauli Ganga, every nook and cranny seems in one way or other to be dedicated to her. The highest and most impressive mountain of the region, Nanda Devi, bears her name. Other peaks too bear her name.

The surrounding Nanda Devi National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1988, safeguards this sacred landscape – home to rare alpine flora, endangered wildlife, and one of the most awe‑inspiring mountain fortresses on Earth.

Treed in legend, the peak is revered by local Bhotiya communities as a goddess, and the Nanda Devi Raj Jat pilgrimage – held once every 12 years -draws thousands of devotees on a spiritual journey through challenging terrain.

Why Was Nanda Devi Closed?

By 1983, growing tourism, unregulated trekking, and ecological stress prompted officials to shut down Nanda Devi National Park and its sanctuary to human activity – including climbing and local grazing.

Decades of research – including wildlife surveys in the 1990s and 2000s – confirmed significant recovery: snow leopards, Himalayan musk deer, and rare alpine flora flourished. Scientists documented over 400 plant species, including 35 medicinal and endangered types, and noted a surge in butterfly and raptor diversity.

“The closure was harsh but needed,” says ecologist Dr. Anjali Sharma. “It gave the ecosystem time to heal.”

While Nanda Devi Main has been closed to climbing since 1983 due to ecological protection measures and its deep cultural significance as a sacred peak, Nanda Devi East remains accessible under strict conditions.

Nanda Devi Main and its inner sanctuary are entirely off-limits to climbing and trekking, forming part of the protected Nanda Devi National Park core zone.

Nanda Devi East, situated in the outer sanctuary, is open to climbing and trekking with special permits from the Indian Mountaineering Foundation and local authorities. Popular routes include the Southeast Ridge, but new route attempts like the 2024 Georgian-led expedition are rare and highly regulated.

This means that while the twin peaks are visually inseparable, their climbing futures differ greatly – with Nanda Devi Main remaining a forbidden goddess, and Nanda Devi East still offering a narrow but precious window for exploration.

Georgian Presence on Nanda Devi East’s New Route Attempt

In 2024, an elite international team – Manu Pellissier (France), Marko Prezelj (Slovenia), and Archil Badriashvili (Georgia) – set out to attempt a bold new route on Nanda Devi East (Sunanda Devi). Their objective was to climb the 7,434 m peak via a direct, technical line that would add a fresh chapter to the mountain’s storied climbing history.

The team advanced to around 5,900 m before retreating due to extreme heat, rapidly melting snow, and dangerous rockfall. Although the main goal eluded them, they turned their energy to unclimbed objectives in the region, successfully completing ascents of Nanda Shori (6,059 m) and Changush (6,322 m). For Georgia, this climb was particularly meaningful: Archil Badriashvili was one of the country’s most accomplished alpinists, known for his cutting-edge alpine-style ascents in remote mountain ranges worldwide. His participation placed a Georgian flag on one of the Himalaya’s most revered summits, even without reaching the top. Tragically, later that same year, Badriashvili lost his life in a mountaineering accident on Shkhelda Peak in his native Svaneti. His work on Nanda Devi East stands as part of his enduring legacy – a testament to his vision, skill, and relentless pursuit of new challenges.

Reopening in 2025: What’s Changing

As of mid-2025, the Indian Mountaineering Foundation (IMF), along with Uttarakhand’s Tourism and Forest Departments, has submitted a proposal to reopen Nanda Devi to controlled mountaineering expeditions for the first time in over four decades.

Approval is pending regulatory review. If passed, climbers will need permits capped at roughly 500 per year. All expeditions must register through sanctioned agencies, include mandatory guides, and operate under strict waste and route management protocols. Nanda Devi’s reopening aligns with Uttarakhand’s broader push toward sustainable adventure tourism, with new access being considered for peaks like Baljuri, Laspad‑hura, Bhanolti, and Rudragaira.

What This Means for Mountaineers

Nanda Devi is not for beginner climbers. Its route demands technical expertise in rock, snow, and ice climbing, with high-altitude fitness essential. Solo climbing is banned; only team expeditions through licensed providers may attempt it.

Veteran mountaineer Shashi Bahuguna called the reopening “a moment of excitement” for Indian and global climbers alike, while others – like Tarun Mahara – cautioned about the lingering risk posed by the long-lost plutonium device.

Beyond adventure, the reopening demands cultural respect. Nanda Devi remains sacred: the upcoming 2026 Raj Jat pilgrimage underscores the mountain’s spiritual prominence. Officials emphasize local participation in tourism planning to ensure benefits are shared with communities from Joshimath, Lata, and Chamoli. Stakeholders have stressed: eco-tourism must uplift, not exploit, local heritage

Agencies propose:

Strict waste guidelines

Timed entry and exit windows

Regular ecological monitoring

Defined base camps and trekking only within core zones

Limits on group size and required porter-to-climber ratios

Local Impact and Jurassic‑Opportunity

Tourism officials anticipate up to 20% growth in adventure tourism to regions like Joshimath, with increased demand for guide services, guesthouses, and eco‑lodges.

While tourists may flock to the Valley of Flowers and Hemkund Sahib, locals emphasize that development must respect environmental carrying capacity.

“We want visitors to cherish Nanda Devi – not harm it,” says elder Gaura Devi, whose community was instrumental in the 1980s Chipko Movement that helped protect the region

Looking Ahead: A New Chapter with Caution

For the global mountaineering community, the reopening of Nanda Devi presents a rare mountaineering offering: height, tech challenge, and cultural depth rolled into one. Yet with that opportunity comes responsibility. This peak’s legacy is not only its height, wildlife, or summit history – but also its rebirth as a sustainable, sacred, and mindful climbing venue. In 2025, Nanda Devi doesn’t just reopen – it starts a careful return, where every climber must respect that the mountain is more than a goal – it’s a guardian.

Comments

1 Comments

Love the article!